原标题:|医师日记|纽约抗疫前哨ICU医师 (连载一) 语音朗诵

在曩昔几个月里,新冠病毒疫情的音讯和报导挤满了每个人的脑际,就像浮游在大海里相同四周只要咸味儿了。

单调的日子只剩下睡觉、吃饭,训练一下四肢,阅读 八卦 新闻;没有其他趣味了。

一位老友共享了这份来自纽约疫情前哨ICU医师的日记,配上语音朗诵,仔细聆听了好几遍,甚是沁入心脾。似乎看到了意大利、纽约那里医院的ICU病房和医护人员抢救患者的一幕一幕情形。

在一、二月武汉的医院ICU病房里,那里的医护人员也应当如此。医师不是天主,但此刻不得不扮演天主选择谁将活下去?

为了生计,美丽的天鹅也会反抗

【语音朗诵】

纽约抗疫前哨ICU医师的日记 |连载一|

First Week of March

N.Y.C. Covid-19 cases, March 1: 1

I am in Karachi, Pakistan, on March 2, when I read the news: New York City has its first patient hospitalized with the coronavirus. Though I am more than 7,000 miles away — reporting on a different disease outbreak — I am already worried about what I will face when I return home in two days to my job as an emergency-room doctor in the city.

纽约ICU医师日记|一|

Even in the best of circumstances, the E.R. can be swamped, with patients doubled up in rooms and too few monitors and beds to go around. Doctors and nurses are always multitasking at the edge of their limits. “ Damage control,” we call it.

I know the situation with Covid-19 is already dire in different parts of the world, Italy especially. Could our hospitals also be overtaken that quickly? What would that look like? I need to know what might come, what decisions I might be confronted with. I want to hear about them directly from health care workers in Italy.

A few days from now, I will come across the name of Guido Bertolini, a clinical epidemiologist who studies intensive care. Through a colleague of his, I reach out to him over WhatsApp, and we begin corresponding. He had been high up in the Italian Alps through the last day of February, when the distressing messages started to come in from colleagues asking him to join a new Coronavirus Crisis Unit for Lombardy, a region in northern Italy. Some of the pleas had an Excel file attached. When Bertolini opened it, he tells me, he couldn’t believe the numbers. He had to see the situation for himself.

With an E.R. doctor from Milan, he drove to the Lombardy city of Lodi the next day. He was horrified by what he witnessed. “ So many patients, in every corner,” he says. “They were attached to oxygen in all possible ways.” Individual oxygen dispensers, meant for single patients, were being split among four people at a time. “When we came out, we were silent for all the journey home,” he says. “We could not speak.” He knows the hospital has already passed its maximum capacity.

意大利疫情——生死攸关!

“From my position in the crisis unit, I see the whole picture,” he says. “Which is dramatic.” Lombardy is one of Italy’s richest areas, where there is “almost no limit in resources,” he explains. Yet the region has only half the number of I.C.U. beds it needs to care for all the critically ill patients infected with Covid-19. He knows doctors are soon going to have to decide who lives and who doesn’t.How could he help them do that?

He begins rounding up — virtually, over Skype — a group of bioethicists and I.C.U. physicians. They include Marco Vergano, a 45-year-old I.C.U. doctor in Turin, in the neighboring province of Piedmont, who is also the chairman of the bioethics group of Italy’s society of intensivists (Siaarti). He’s working back-to-back shifts in the I.C.U., but he jumps online with the six other members of the task force that Bertolini has set up. That night, he begins drafting a document. The first version includes strict criteria:

If you are over 80 or one of your organs isn’t functioning well or your dementia has advanced past a certain point, you are unlikely to get a breathing tube or a spot in the I.C.U.

Soon after, the group decides to delete the specific cutoffs, so that hospitals can adapt their responses to circumstances, which are changing hourly. They want doctors to have flexibility but use these principles to guide and justify their decision-making. The document’s fundamental thrust, though, is that those with the highest chances of survival— the young and the healthy — get priority. They strongly advise against allocating precious resources, like ventilators and beds, on the traditional basis of first-come, first-served, which would reduce the number of lives a hospital could save. “ Soft utilitarian” is how Vergano characterizes the approach.

Swift and fierce denunciation of the group and its recommendations follows the document’s release. “You cannot imagine to what extent we have to face harsh criticism,” Vergano says. “From colleagues to journalists to bioethicists — we are in firing lines these days,” Bertolini adds. “ They say we are God-playing.”

Vergano notes that most of the criticism has come from regions in Italy that have yet to be hit as hard as Lombardy. They are“completely living in another world,” Bertolini says, because “ unless you are inside this situation, you cannot understand fully.” People are, it seems, woefully bad at grasping how future events will unfold, whether in the city next door tomorrow or across the Atlantic a couple of weeks later.

Back in New York, I work a couple of shifts in the E.R. Though we’ve been given updated instructions for screening patients for coronavirus — which say that a person need not have a history of recent travel to qualify for testing — the hospital feels mostly like its normal, hecticself, as it did before I left the country.

待续:纽约ICU医师日记|二|

Second Week of March

N.Y.C. Covid-19 cases, March 8: 1

全球医师安排微信渠道

我的医师® 资讯超市

所有人都熟知超市,各取所需,拿货付款走人。若把日用百货瓜果蔬菜换成资讯产品,便是“资讯超市”了。

春 天

责任编辑:

早X背后的“隐形推手”是?爱廷玖达泊西汀片为爱延时

早X背后的“隐形推手”是?爱廷玖达泊西汀片为爱延时 科学治疗早X,可以试试爱廷玖盐酸达泊西汀片

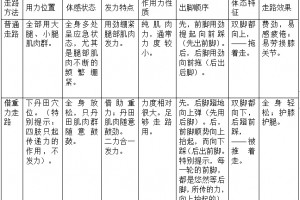

科学治疗早X,可以试试爱廷玖盐酸达泊西汀片 借重力走路

借重力走路 辅助生殖供给缺口巨大,新宝恩引领试管助孕行业良性发展

辅助生殖供给缺口巨大,新宝恩引领试管助孕行业良性发展 国货自信潮起,汇仁药业以5°青年文化加速品牌认知进阶

国货自信潮起,汇仁药业以5°青年文化加速品牌认知进阶 汇仁药业开学季喊话年轻人:自信上场,家人是你的坚强后盾

汇仁药业开学季喊话年轻人:自信上场,家人是你的坚强后盾 津药达仁堂集团携手张仲景开启"胃肠同治新时代",以新营销实现共赢共进

津药达仁堂集团携手张仲景开启"胃肠同治新时代",以新营销实现共赢共进 朗圣药业打破沟通壁垒:沉浸式沟通成新趋势,玩转年轻化营销

朗圣药业打破沟通壁垒:沉浸式沟通成新趋势,玩转年轻化营销